There’s a romantic picture of the typical man (or single mother) living below the poverty line. Down on their luck, abused by an uncaring and unjust system, struggling (and perhaps, in times of extreme need, stealing) to get food on the table. Millions of Robin Hoods, basically.

The poor are supposed to be more or less identical to the non-poor, in temperament and habit. The non-poor are supposed to be a bad day away from tripping into the underclass.

Some percentage of poor people are really there due to bad luck. That percentage, I assume, are the ones that tend to clamber back towards the middle class. Or out of poverty, at least. If not them, perhaps their children.

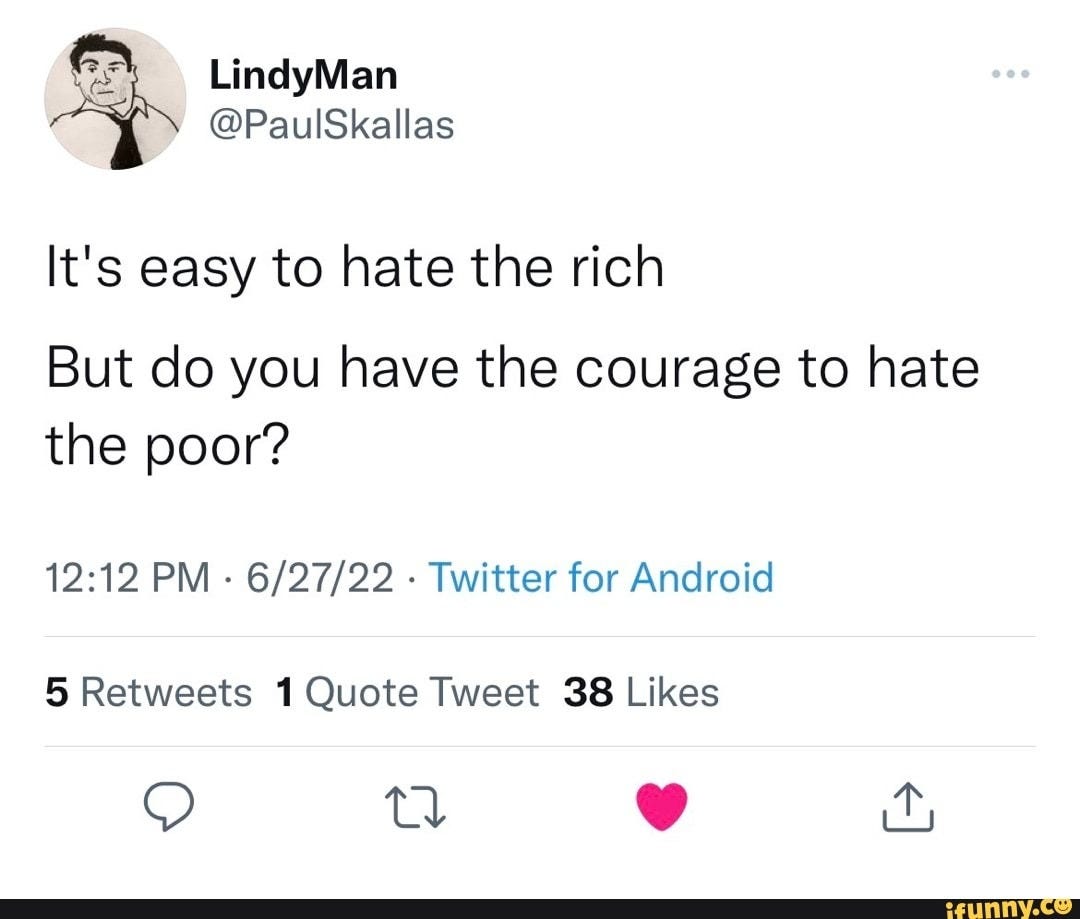

But another percentage of the poor are there due to their own decisions. Caleb Hammer’s YouTube show, Financial Audit, is detested by BlueSky lefties for exposing this fact. Guest after guest airs their crippling debt: $25,000 or $300,000 in the hole and still digging deeper. Over half a million dollars on, among other expenses, Taylor Swift tickets. You could fill a bingo card with the interviewees’ bad choices: Doordash, Klarna, puppies, European vacations, online sports betting.

“Hillbilly Elegy,” Vice President JD Vance’s 2016 memoir, makes no secret of the things poor people do that keep them poor. Vance says he lived in “a world of truly irrational behavior.”

“We spend our way into the poorhouse. We buy giant TVs and iPads. Our children wear nice clothes thanks to high-interest credit cards and payday loans. We purchase homes we don’t need, refinance them for more spending money, and declare bankruptcy, often leaving them full of garbage in our wake. Thrift is inimical to our being. We spend to pretend that we’re upper-class. And when the dust clears—when bankruptcy hits or a family member bails us out of our stupidity—there’s nothing left over. Nothing for the kids’ college tuition, no investment to grow our wealth, no rainy day fund if someone loses her job. We know we shouldn’t spend like this.”

“Our homes are a chaotic mess. We scream and yell at each other like we’re spectators at a football game. At least one member of the family uses drugs—sometimes the father, sometimes the mother, sometimes both. At especially stressful times, we’ll hit and punch each other, all in front of the rest of the family, including young children; much of the time, the neighbors hear what’s happening. A bad day is when the neighbors call the police to stop the drama. Our kids go to foster care but never stay for long. We apologize to our kids. The kids believe we’re really sorry, and we are. But then we act just as mean a few days later.”

“We don’t study as children, and we don’t make our kids study when we’re parents. Our kids perform poorly in school. We might get angry with them, but we never give them the tools—like peace and quiet at home—to succeed. Even the best and brightest will likely go to college close to home, if they survive the war zone in their own home.”

“We choose not to work when we should be looking for jobs. Sometimes we’ll get a job, but it won’t last. We’ll get fired for tardiness, or for stealing merchandise and selling it on eBay, or for having a customer complain about the smell of alcohol on our breath, or for taking five thirty-minute restroom breaks per shift. We talk about the value of hard work but tell ourselves that the reason we’re not working is some perceived unfairness,” Vance writes.

Vance refers to “hillbilly values,” and not always derisively. He “learned to value loyalty, honor, and toughness.”

“[D]espite all of the environmental pressures from my neighborhood and community, I received a different message at home. And that just might have saved me,” Vance concludes.

Thomas Sowell famously proposed that black American “ghetto culture” descended from certain British groups which had moved to the American South.

Keep all this in mind as we turn to an incredible, and highly amusing study published in the British Journal of Political Science.