Rudolph The Redpilled Reindeer

Rudolph is esteemed not because he’s different, but because he’s useful.

Rudolph took off in frantic fashion after World War II.

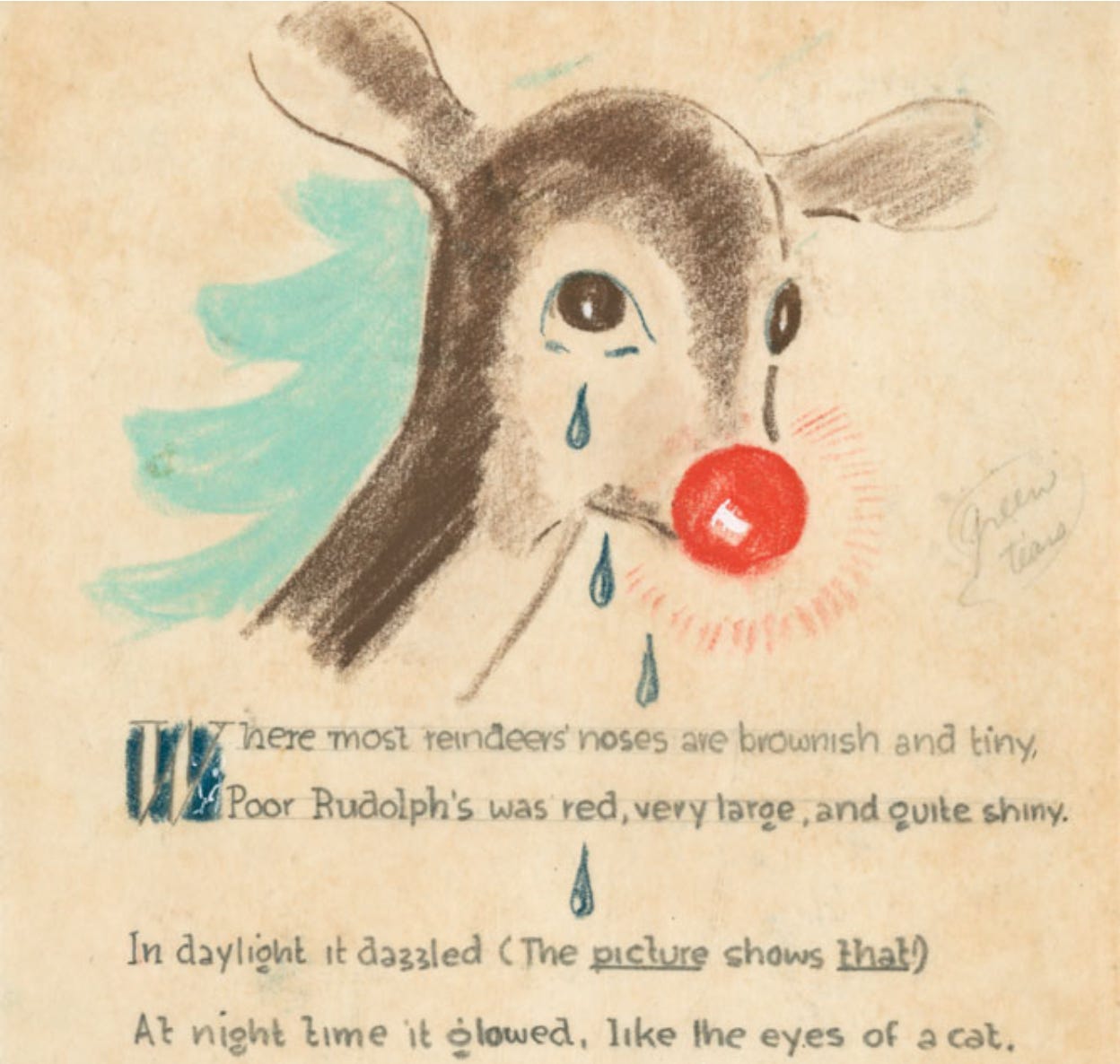

The fictional reindeer was the 1939 creation of Robert L. May, working for a department store chain in Montgomery Ward. Postwar abundance meant Rudolph books, comics, toys — then a hit song written by Johnny Marks and performed by country-music star Gene Autry.

Autry’s version of “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” was the No. 1 song in America the week of Christmas 1949.

“By 1985, when Marks died at 75, there reportedly were some 500 versions that tallied 150 million records sold. Marks had sold as many as eight million copies of the sheet music and 25 million copies of orchestral and choral arrangements,” says The New York Times.

The Rudolph story is of enduring appeal to American children. Why?

“Much like the modern Santa Claus song, Rudolph’s story is for children; more specifically, it is a children’s story about overcoming adversity and earning, by personal effort, respect in the adult world,” wrote Ronald Lankford in his 1962 book “Sleigh Rides, Jingle Bells, and Silent Nights: A Cultural History of American Christmas Songs.”

“As a young deer (child) with a handicap that turns out to be an unrecognized asset, Rudolph comes to the rescue of an adult (Santa) at the last minute (on Christmas Eve). When Rudolph saves the day, he gains respect from both his peers (the reindeer who refused to include him in games) and the adult world.”

“The story of Rudolph, then, is the fantasy story made to order for American children: each child has the need to express and receive approval for his or her individuality and/or special qualities. Rudolph’s story embodies the American Dream for the child, written large because of the cultural significance of Christmas.”

Lankford’s analysis gets us closer to understanding Rudolph’s appeal, but declines to investigate the less cheery implications of the narrative.