“A long way out in the deep blue sea there lived a fish. Not just an ordinary fish, but the most beautiful fish in the entire ocean. His scales were every shade of blue and green and purple, with sparkling silver scales among them.”

So begins “The Rainbow Fish,” a 1992 children’s book written and illustrated by Marcus Pfister and translated into English by J. Alison James. Pfister’s illustrations are enormously appealing to children, probably because of the titular Rainbow Fish’s shiny foil scales.

I’ll concur with the Makers of Discourse on X: “The Rainbow Fish” is evil.

But first, a summary.

We learn that Rainbow Fish’s plain-scaled peers admire his beauty, and want to befriend him, but Rainbow Fish is too proud to acknowledge them. We are compelled to believe this characterization of Rainbow Fish because the story is told from the third-person omniscient perspective. The author is empowered with absolute authority.

Eventually, a little fish works up the nerve to ask Rainbow Fish for one of his shiny scales. Rainbow Fish rebuffs him, harshly, and the little fish reports back to the other plained-scaled fish, who begin harshly shunning Rainbow Fish.

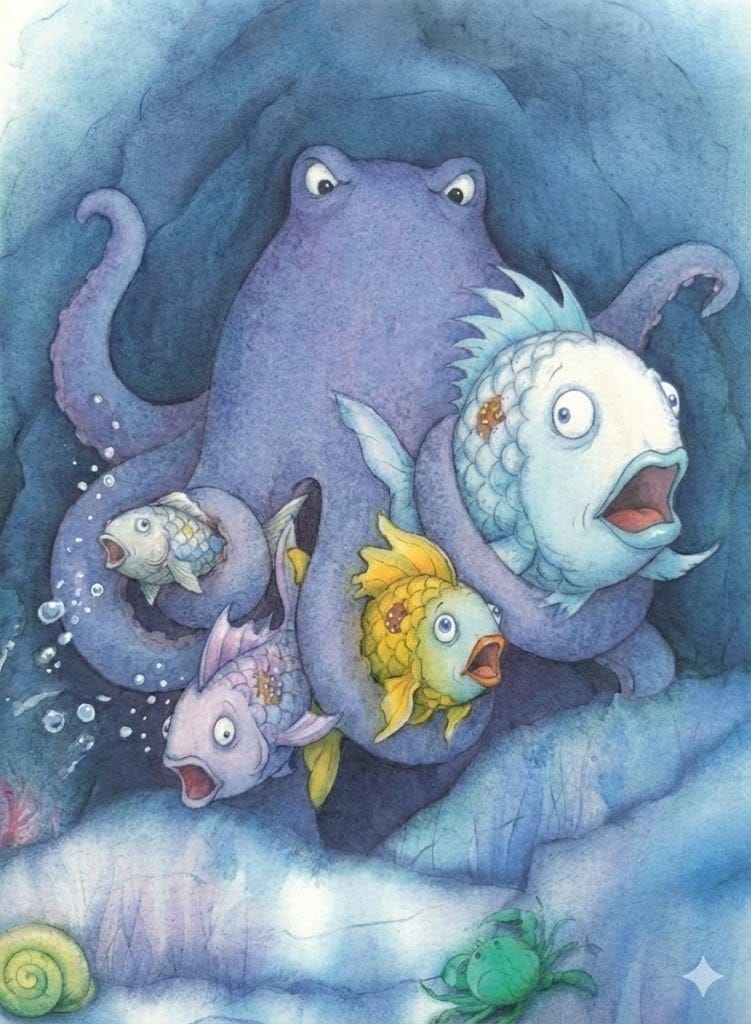

Rainbow Fish is perturbed and seeks guidance from an oracle-like octopus lurking in a dark cave.

“I have been waiting for you … The waves have told me your story. This is my advice. Give a glittering scale to each of the other fish. You will no longer be the most beautiful fish in the sea, but you will discover how to be happy,” counsels the leviathan.

Rainbow Fish is initially disturbed, but comes around to the idea, and distributes his shiny scales among the fish, earning their friendship. He is happy. The End.

In other words: “You will own [no shiny scales], and you will be happy.” My preferred ending would see the conniving octopus devouring the now poorly camouflaged school of fish.

“The Rainbow Fish” strikes me as a plainly communist morality tale. Some are born more beautiful than others, the plot concedes — But beautiful people must work to “redistribute” nature’s gifts, even, or especially, if that means disfiguring themselves.

Obviously, “The Rainbow Fish” doesn’t introduce kids to historical materialism or speculate as to the coming bourgeois revolution. But “The Rainbow Fish” happily indulges in the spirit of communism: resentment.

To quote Mystery Grove, “Reminder: Communism is when ugly deformed freaks make it illegal to be normal then rob and/or kill all successful people out of petty resentment.”

To quote Gore Vidal, “Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.”

You can abolish private property or “tax the billionaires” all you like. Nature’s inequalities persist.

There are solutions for wrangling them, of course. The Rainbow Fish’s peers used social pressure to convince him to mutilate himself. But what if he had refused their coercion?

You can imagine the other fish banding together and murmuring, under cover of darkness, “We need to kill the Rainbow Fish.”

But there’s a less bloody solution for total equality.